This article was written by Ron Spomer and posted on SportsAfield. Thank you, Ron for the great story.

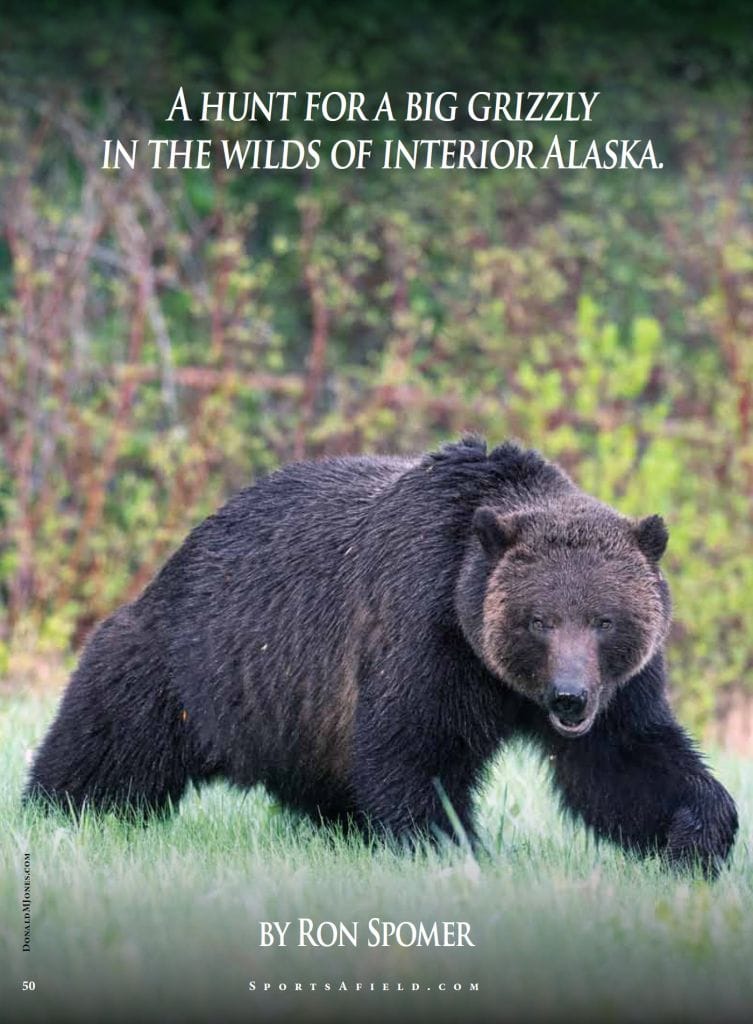

June is late for hunting interior grizzlies in Alaska, but last year I took advantage of an extended season in the Upper Mulchatna River drainage designed to take out old, carnivorous bears that had perfected the killing of moose and caribou calves. Some of these bruins had become so effective that they were eating as many as twenty calves in a season. The moose population in the drainage had nose-dived and was not bouncing back. So in the spirit of helping the moose, I headed north to look for a big grizzly.

There was an unexpected bonus to the hunt: my old friend, master guide and veteran bush pilot Jerry Jacques would be flying me, along with a packer and guide, to bear camp. I was pleased when Tim Winslow, head operator at Bushwhack Alaska Adventures Talarik Creek Lodge, told me Jerry would be flying us in. Any Alaska bush pilot who has survived tens of thousands of off-runway landings is a careful, cautious pilot, which is not to say Jerry hasn’t had a “hard landing” or two in his many decades of service.

Guide Gary Stewart directed us to a shallow lake an hour’s flight from Taralik Lodge. Its bottom was deep with muck. We discovered this when Jerry’s Beaver slid to a stop a hundred yards from shore. We were already wearing waders, so we stepped out of the plane and began slogging our gear to shore. Gary had packed a luxury wilderness camp: A large Stone Glacier tent with floor and cots; a separate two-man tent for our packer, Jonah; and a variety of food including not just the usual freeze-dried meals, but frozen salmon filets and bacon. There were even three light, comfortable camp chairs from which to glass.

And did we ever glass. Look, look, look for hours, and then look some more. This hunt was all about letting our binoculars do the walking. Spring grizzly bears are famously peripatetic, striding across miles and miles of tundra, taiga forest, bogs, fens, and muskeg flats, looking but mostly sniffing for two things: food and mating partners. To find a killer bear, we needed a room with a view.

“That tundra bench looks about right,” Gary said after Jerry departed. He nodded me toward a distant opening above the spruce forest hugging the lakeshore. “Clear views of the lakes and bog, plus all those open ridges above.”

We hauled the gear up in two half-mile trips along a shoreline bear trail, then 100 feet up, set up the tents, fired up the stove, and began glassing. “Wouldn’t it be wild to spot our bear right from camp?” I said.

“That’s the plan. But we’ll probably have to move a bit, too. We’ll see.” Given the volume of country, backpacking to find a bear would be a high-energy enterprise. But if we didn’t spot a “camp bear” in a day or two, we’d likely have to pack a more spartan camp and hump it to a new location. We had ten days.

The setting was classic central Alaska wilderness: dry tundra ridges blanketed with crowberry, bearberry, cranberry, and caribou lichen spilling downslope into a spruce, birch, and willow forest. A languid stream flowed quietly through brushy meadows into a small pond that seeped through a flat, mossy cottongrass bog to the main lake where tundra swans battled noisily for nesting territory and small rafts of greater scaup patrolled the open water. They competed with pintails, shovelers, mallards, and green-winged teal. Black-and-white Bonaparte’s gulls flitted like terns, carrying nesting material to boughs atop the tallest spruces while a bald eagle kept a hungry eye on everything.

“What’s making that call?” assistant guide Jonah asked at sunrise our first morning.

“Not sure. Red-necked grebe, I think.” It was. A mated pair entertained us hourly, dragging pond lily leaves and stems into a floating nest. Scaup were also building their nests in the flooded shoreline grass.

The three of us spent our first full day atop a tundra flat a quarter-mile from camp, glassing the entire valley plus an open ridge and an intersecting valley some two miles away. After each quarter hour of scouring the empty landscape for bears, it was hard to resist a peek at the lake activity.

“Those gulls are trying to grab some mallard ducklings,” Jonah announced.

“Seems early for ducklings,” I replied. “The grebes and gulls are still building their nests.”

“Yeah, but there they are. Just popping out of the grass on the edge of the water.” A pair of big herring gulls were hawking over the spot, but the ducklings had apparently burrowed into the vegetation. After the marauders left, the little mallards reappeared on the lake in the hen’s wake.

As the earth slowly rotated out from under the sun’s glare, we re-hunted and re-shot many of the game animals from our pasts, then began re-catching fish. Meanwhile, Gary never took the binocular from his eyes. The guy was relentless.

When I commented on the inactivity of this hunt, he said, “You should have been with us last week. Cloudy, rain, and fifty-mile-an-hour winds nearly the whole week.”

“With that enlightenment, I’ll take sunshine, gentle breezes, these glassing chairs, lunch, and inactivity,” I said. “Thank you.”

After again scanning all likely and available bear terrain, I turned back to the lake and then spotted a golden eagle and a pair of harriers. There were even robins, looking out of place so far from bluegrass lawns. Gray jays, white-crowned sparrows, and a rare boreal chickadee sang and flitted through. Tree swallows swooped near, catching mosquitoes, we hoped, even though we were well protected under head nets.

My chief diversion during glassing breaks was slapping mosquitoes from my knee. Something about the black material on my pants attracted them. The satisfaction of flattening as many as fourteen in a whack was addictive.

“Your license allows you unlimited mosquitoes,” Gary said.

“There’s a bear!” Jonah said. “Bottom of that far tundra ridge.”

“Oh, yeah. Big bear on a mission.” It had dark chocolate legs, a blond back, and was easy to spot despite the nearly two-mile distance.

“No sense going after him,” Gary advised. We didn’t argue. This bear showed no signs of pausing, let alone stopping. He was a classic spring bear on the move. “We might move to that farthest open hill to the south tomorrow. That might put us close enough to catch him if he comes back on that route.”

“Or maybe his rounds will bring him past here,” I said.

“Good a chance as any.”

“Hey, there’s a moose. Bull. Coming off the slope into the creek bottom.”

“I see him,” Jonah said.

Gary focused his spotting scope on the bull. “Good fronts on him already. Looks like three points. Might want to look for him this September.”

“If that grizzly doesn’t find him first.” Some grizzlies have been recorded killing adult moose almost as easily, if not as frequently, as calves.

We hiked back to the tents for a late dinner, the caribou lichens crunching underfoot. The tundra was excessively dry, but the lichens were larger and more abundant than I’d seen them in years. The wildflowers—which included pink crowberry, purple saxifrage, white Labrador tea—were few, weak, and drying. The land needed rain. Johan hiked down to the pond for camp water every evening, straining it through a gravity filter.

After dining and swatting the mosquitoes that had slipped into the tent with us, we decided we would hike to the new lookout point in the morning. After coffee and breakfast, we stuffed extra food and water in our packs. I’d shouldered my rifle and was just tightening my hip belt when Gary made an announcement over the wilderness intercom: “There’s our bear.” He put enough intensity in the statement that we knew it was no joke.

The bear, some 700 yards away, was big enough that I didn’t need directions for finding it strolling along the upper lake. “That’s the same bear as yesterday. Let’s go!”

A steady breeze wafted from the east. The bear was marching west. We hurried north to cut him off. Down through the dwarf birch, into scattered spruce, through a willow thicket. We broke out in the wide-open bog without pausing. We had to cover some 300 more yards before the bear covered the same distance and disappeared into a spruce forest.

It was like walking on a wet mattress, our boots sinking ankle-deep in soggy mosses and cotton grass. The bear flashed in and out of clumps and clusters of willows and young spruce, glancing at us, but showing no signs of spooking. We paused for a short breather, then pressed on until we had closed the distance.

“How far?” I didn’t want to mess with my range finding binocular when it was the rifle that needed attention. I slipped it off my shoulder, knelt, spread my shooting sticks, and chambered a round in my .338 Federal.

“One-eighty-nine.”

“Stop him.”

Gary whistled. The bear looked, but kept striding, miles to go before he’d sleep. Gary whistled more loudly. The bear stopped. I settled the reticle on his shoulder, but before I could break the trigger, he resumed his trek and disappeared behind a cluster of birch. Then he reappeared, head swaying, looking toward us. The cross wind held steady.

“Louder.” I said. Gary blasted out his sharpest whistle yet. The bear stopped and peered at us, and the rifle boomed.

“Hit him again,” Gary said. The bear was spinning in a tight circle, biting at what had bit, his leg flopping, broken. I’d already racked another round. By the time I launched it, the grizzly had all but screwed himself into the bog. My shot went high, but it was enough to inspire the stricken bear to limp for the dense forest. He was behind a few small spruce trees, going straight away. I had no shot.

But Gary had an opening, and I’d already given him clearance to anchor any wounded bear that appeared to be escaping into cover. At the boom of his .375 Ruger, the bear rolled up, hip broken. I put a finisher high in his shoulder, cutting the spinal column.

All was quiet save the background whine of the mosquitoes. “He’s finished, but refill your magazine and be ready,” Gary said. But there was no need. The bear was most sincerely dead.

“Look at the head on him!” Gary exclaimed as we relaxed and started admiring the bear.

“That’s one big noggin.” Big enough, in fact, to land a spot in Boone and Crockett. The back half of the pelt had been rubbed of all guard hairs, exposing scars and bite marks, one fresh. A chunk of the bear’s upper lip was freshly notched.

“He either dated a reluctant sow or contested another bear for her favors,” I said. “Wonder how many moose calves he’s accounted for over the years?”

My initial shot had pulverized the front leg. I found the bullet lodged against the hide in the far shoulder pocket. Gary’s shot had broken the bear’s left hip, ending its drive for the woods.

“Lucky he didn’t get to the trees,” Jonah said. “Man, that’s thick!”

“We’d have been inside of thirty, maybe twenty feet before we could have seen him,” Gary said.

“Well, thanks to your anchoring shot, we don’t have to worry about that now,” I said. “Let’s get to skinning, then radio Jerry for an extraction. I hear there are fish to chase back at the lodge.”

Loaded for Bear

The Parkwest Arms SD-97 in .338 Federal I carried is a welcome blend of traditional and modern. The Mauser-style, controlled-feed short action picks rounds from the five-round, flush, hinged-floorplate magazine with authority, clutches them tightly to the bolt face for straight-line delivery into battery, and extracts them positively. The standing blade ejector kicks empties as fast and far as your cycling action powers them. A McMillan hand-laid synthetic stock requires no weather protection. Nor does the CeraKote finished stainless steel barreled action. It’s perfect for wet-weather Alaska. The slim, trim lines help the rifle slip through cover without snagging. The beautifully balanced rifle carries comfortably and swings into action quickly. The minimal recoil of the .338 Federal loads, a touch less than that of a .30-06 pushing a 180-grain slug, aids the quick follow-up shots sometimes needed on a bear encounter. The rifle’s weight with sling and Leupold VX-3HD scope aboard comes to 8 pounds, 7 ounces. Every ounce of this is made right here in the USA.

The little-known .338 Federal is a SAAMI-approved, commercial iteration of an old wildcat that simply flares a .308 Winchester case mouth to hold .338-inch bullets. About 47 grains of Winchester 748 powder can drive a 210-grain bullet as fast as 2,530 fps. Ward Dobler of Parkwest Arms loaded 210-grain Barnes TSX to 2,490 fps average muzzle velocity, more than fast enough to do just what it did—break major bones and penetrate to the far side hide of a big, tough grizzly. Older or small-framed hunters looking for good terminal performance without excessive recoil might consider the .338 Federal. It’s a sleeper that deserves to be awakened.—R.S.

Adventure in Alaska

Bushwhack Alaska Adventures is under new management, Kip Fulks and Tim Winslow, who employ an outstanding crew of polite, respectful, serious, and intelligent young guides. Taralik Lodge, perched on a bluff above vast Iliamna Lake, has been a fixture in the area’s hunting and fishing industry for decades. Bushwhack Alaska offers spring and fall grizzly, brown bear, and black bear hunts, fall moose hunts, and seasonal fishing. After the bear hunt, my wife and I sampled grayling, rainbow trout, lake trout, and northern pike action from fast, comfortable boats. We were two weeks too early for the first salmon runs, but those keep the place hopping from early July through September: bushwhackalaska.com.—R.S.